The Catalogue

This is a chronological catalogue of what we have available online in the EUVS Digital Collection. Check back regularly as we add more titles to this very important collection of bartending and distilling knowledge.

Want to read what’s inside a volume? Click the book cover to enter.

1712

Nouvelle instruction pour les confitures, les liqueurs et les fruits

Chef du cuisine to dukes, cardinals, marquises, and a regent François Massialot inspired professional chefs not only in France but in as well, especially when his Nouveau cuisinier royal et bourgeois was first published in 1691. Expanded into three volumes by 1734, the English version—The Court and Country Cook—was printed in numerous editions from 1702 until the mid-1750s.

Chef du cuisine to dukes, cardinals, marquises, and a regent François Massialot inspired professional chefs not only in France but in as well, especially when his Nouveau cuisinier royal et bourgeois was first published in 1691. Expanded into three volumes by 1734, the English version—The Court and Country Cook—was printed in numerous editions from 1702 until the mid-1750s.

Massialot’s lesser cookbook Nouvelle instruction pour les confitures, les liqueurs et les fruits fist appeared in 1692 as an anonymous edition published in Paris by Charles de Sercy. Brimming with recipes for liqueurs, eaux-de-vie, espirit de vin, ratafias, distilled botanical waters, and hypocras, this volume is another inspiration for bartenders aspiring to create new ingredients.—Anistatia Miller

1753

The New English Dispensatory

In this 1753 edition of The New English Dispensatory a simple Stomach Julep (Julepum Stomachicum) appears with some fascinating ingredients: a saffron syrup made with sherry, spirit rectified with mint, and a non-alcoholic mint distillate.

In this 1753 edition of The New English Dispensatory a simple Stomach Julep (Julepum Stomachicum) appears with some fascinating ingredients: a saffron syrup made with sherry, spirit rectified with mint, and a non-alcoholic mint distillate.

From this recipe you can well imagine why it’s worth flipping through the pages upon pages of medicinal simples compiled original by John Quincy and later improved upon by William Lewis to inspire your mad-scientist aspirations.—Anistatia Miller

1757

The Complete Distiller

There is no other way to describe distiller Ambrose Cooper’s comprehensive book entitled The Complete Distiller except to quote the title page describing its contents:

There is no other way to describe distiller Ambrose Cooper’s comprehensive book entitled The Complete Distiller except to quote the title page describing its contents:

“1. The method of performing the various processes of distillation with description of several instruments: The whole doctrine of fermentation; The manner of drawing spirits from malt, raisins, molasses, sugar, etc. and of rectifying them; With instructions for imitating to the greatest perfection both colour and flavour of French brandies.

“2. The manner of distilling all kinds of simple waters from plants, flower, etc.

“3. The method of making compound waters and rich cordials largely imported from France and Italy as likewise all those now made in Great Britain.”—Anistatia Miller

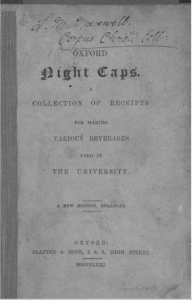

1827

Oxford Night Caps

1835

Oxford Night Caps

1847

Oxford Night Caps

This is the first known—to date—volume dedicated entirely to mixed drinks in the English language.

This is the first known—to date—volume dedicated entirely to mixed drinks in the English language.

Oxford Night Caps: A Collection of Receipts for Making Various Beverages Used in the University was published a number of times between 1827 and 1931 to aid Oxford University students in mixing proper beverages for their on- and off-campus gatherings. The soft cover format remained the same from edition to edition and so did the drinks for the most part.

In this 1847 edition, ice was usually not part of the formula. Dilution relied on room temperature water. (Remember that room temperature in England is much lower than in other climes.) So ice didn’t enter the picture until the turn of the century. Rumfustion and a few dozen punches are worth revisiting today. So are the lower alcohol cups.—Anistatia Miller

1851

The Modern Housewife or Ménagère

In his 1851 runaway best-seller, The Modern Housewife or Ménagère, Soyer offered up recipes for Gold Jelly, made with eau-de-vie de Danzig; a Maraschino Jelly imbued with quartered fruits; and Rum-Punch Jelly.

In his 1851 runaway best-seller, The Modern Housewife or Ménagère, Soyer offered up recipes for Gold Jelly, made with eau-de-vie de Danzig; a Maraschino Jelly imbued with quartered fruits; and Rum-Punch Jelly.

This concept was grabbed up by Jerry “The Professor” Thomas and was crafted into a sherbet-with-cognac and Jamaican rum #28 Punch Jelly. The American mixologist commented in his 1862 The Bar-Tender’s Guide that: “This preparation is a very agreeable refreshment on a cold night, but should be used in moderation; the strength of the punch is so artfully concealed by its admixture with the gelatine, that many persons, particularly of the softer sex have been tempted to partake so plentifully of it as to render them somewhat unfit for waltzing or quadrilling after supper.”

London’s most famous French chef of the period, Alexis Benoit Soyer (1810-1858), was another mixed drinks champion. At the height of his career, Soyer earned more than £1,000 per year as the Reform Club’s chef: an outrageous sum of £100,000, if calculated in today’s market. He created the sumptuous Reform Raclettes of Lamb still served in London’s Reform Club. He designed the template for what would become the standard “modern” kitchen. He built an efficient, portable soup-kitchen that was stationed at the Royal Barracks in Dublin and fed 26,000 Irish Potato Famine victims daily. He developed commercial products such as Soyer’s Sauce and Soyer’s Nectar. He also created fanciful potables that may sound all too much like the 1970s through 1990s: Jelly Shots and blue drinks.

First the blue drinks. The popularity throughout Britain of Schweppe’s fizzy drinks in glass bottles inspired Soyer to team up with the Carrera Water Manufactory & Company to create his own branded sparkling water, a sparkling lemonade, and a new soft drink: Soyer’s Nectar. Composed of raspberry, apple, quince, and lemon juices, spiced with cinnamon, and tinted bright lake blue, the carbonated drink was a trendy hangover cure for novelty-obsessed Victorians. By 1850, The Sun declared it far better than Sherry Cobbler. The Globe recommended adding a tot of rum and dubbed Soyer the “Emperor of the Kitchen”. His own advertisements suggested that “It may also be taken just previous to going to bed, with a glass of wine, such as Sherry, Madeira, etc, or of any spirit or liquor mixed in it, and drinking as much of it as possible as a draught.” The same promotion included recipes for three types of Cobbler.

Author Ruth Cowen related another of Soyer’s contributions to the drinks world in her 2006 biography Relish: The Extraordinary Life of Alexis Soyer: his introduction of an American-stye bar in the configuration of a six-star restaurant. The same year that Prince Albert opened the Great Exhibition of 1851 and its fabulous Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, Soyer opened Soyer’s Universal Symposium of All Nations where the Albert Hall now stands.

Reached via a wooden staircase in the building that was once Gore House, Soyer created an experience that would be grand spectacle today. Each room was lavishly decorated: one as a Chinese boudoir, another as a grotto, another a dungeon. One room boasted a table covered by a 400-foot-long tablecloth that sat 500 people. Amongst these settings he opened The Washington Refreshment Room with a beverage menu that offered up 40 different concoctions, including Hailstorms, Mint Juleps, and Brandy Smashes plus some of Soyer’s own inventions such as his Nectar Cobblers and Soyer au Champagne.

Although he had interviewed “an eccentric American genius, who declared himself perfectly capable of compounding four [cocktails] at a time, swallowing a flash of lightning, smoking a cigar, singing ‘Yankee Doodle’, washing up the glasses, and performing the overture to the Huguenots on the banjo simultaneously”, he selected a West Londoner named William York to head his bar. Was that American Jerry Thomas? It’s highly unlikely as he had sailed from New York for San Francisco in 1849, and did not visit London until 1859 (at which point he was impressed enough with Soyer’s work to include six of his recipes in his 1862 book).

The Universelle Symposium closed before the year was out due to massive financial complications. It left Soyer free to join his close friend Florence Nightingale in the Crimea, where he devoted his remaining days to developing military cooking equipment designed to provide healthy, efficiently-prepared meals for the troops. His Soyer Stove was readily adapted by British military personnel around the world. The unchanged design was used during the 1982 Falkland War. You can even see a cluster of them in the Michael Caine film Zulu. —excerpted from Spirituous Journey: A History of Drink, Book Two by Jared Brown & Anistatia Miller (2010)

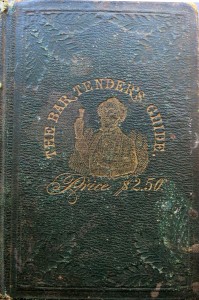

1862

The Bar-Tender’s Guide or How to Mix Drinks

The first drinks book in the English language to contain recipes for cocktails, The Bar-Tender’s Guide or How to Mix Drinks by Jerry “The Professor” Thomas (later retitled How to Mix Drinks or the Bon-Vivan’ts Companion) presented the broad variety of mixed drinks that had gained rapid popularity in the United States by the early 1860s.

Ten cocktails appear in this landmark work: Brandy, Champagne, Fancy Brandy, Fancy Gin, Gin, Japanese, Jersey, Soda, The, and Whiskey. Thomas’s travels to England in 1859 where he appeared as a guest barman at the Bowling Alley Bar in London’s Cremorne Pleasure Gardens yielded a few adaptations of British drinks such as Gin Punch by [Alexis Benoit] Soyer.

Punch Jelly, another Soyer-influenced concoction comes with the caution that: “the strength of the punch is so artfully concealed by its admixture with the gelatine, that many persons, particularly of the softer sex have been tempted to partake so plentifully of it as to render them somewhat unfit for waltzing or qua drilling after supper.”

Bottled cocktails and punch to speed up service are also introduced in this amazing mixed drink bible.

Thomas’s publisher printed an 1876 edition during the barman’s lifetime and two years after his death, published a posthumous edition in 1887 that included numerous popular drinks of the late 1880s. —Anistatia Miller

1863

Londoners Henry Porter and George Roberts were not fans of the new American bars nor of cocktails that were displacing traditional British compounds such as punches and cups. By 1860s, the colonial intrusion into British drinking habits insinuated by Reform Club chef Alexis Benoit Soyer, Leo Engels at the Criterion, the Bowling Alley Bar at the Cremorne Pleasure Gardens led these to authors to comment:

Londoners Henry Porter and George Roberts were not fans of the new American bars nor of cocktails that were displacing traditional British compounds such as punches and cups. By 1860s, the colonial intrusion into British drinking habits insinuated by Reform Club chef Alexis Benoit Soyer, Leo Engels at the Criterion, the Bowling Alley Bar at the Cremorne Pleasure Gardens led these to authors to comment:

For the ‘sensation-drinks’ which have lately travelled across the Atlantic we have no friendly feeling . . .we will pass the American bar . . .and express our gratification at the slight success which “Pick-me-up,” “Corpse-reviver,” “Chain-lightning,” and the like, have had in this country.

Generally, British tastes were not attuned to the sweet offerings of the American cocktail menu nor the tooth-numbing coldness at which they were served. Thus, Cups and Their Custom (aka: Drinking Cups and Their Custom) offers a view into a world of lower alcohol strength drinks that rely more on spice and complexity than on heavy citrus and heavier spirit ratios.

Besides wine-based cups and a variety of punches a few other classic British compounds are presented: wassail, lamb’s wool, metheglin, dating back to medieval and Elizabethan times. Ales and beers play a primary role in a few of these concoctions. There are even a handful of essential liqueur recipes as well as a formula for a blood-warming Hunting Flask.

This book was so popular that a second edition was published in 1869.

As the bar world looks for inspiration in creating lower-alcohol drinks as well as beer-based offerings, this book becomes a tempting inspiration for drinks development.—Anistatia Miller

1869

Cooling Cups & Dainty Drinks

Cooling Cups & Dainty Drinks

Written by William Terrington, in 1869, Cooling Cups and Dainty Drinks is the earliest British publication to document cocktail recipes along with classic British and European mixed drinks. (This is the 1872 edition.)

In addition to a Gin Cocktail made with ginger liqueur (the Gin Cocktail cocktail referred to in a 1798 British Newspaper that was “vulgarly called ginger”), there are a couple of drink recipes that were formulated by Britain’s first celebrity chef Alexis Benoit Soyer back in the 1850s, which were also featured in Jerry Thomas’s 1862 Bar-Tender’s Guide.

So popular was this volume as the British public became aware of American-style iced drinks while still embracing time-honoured British classics that to was published again in 1872 and 1890.—Anistatia Miller

Haney’s Steward & Barkeeper’s Manual

Haney’s Steward & Bartender’s Manual was one of many titles Jesse Haney & Co., Publishers produced for the trade. The reason this sample 82-page volume is of interest is because cocktail book collectors such as Mauro Majoub and drinks historians Jared Brown, Anistatia Miller, and Dave Wondrich believe this work may be the book that Harry “The Dean” Johnson referred to as his very first and earliest work. No one will ever know for certain. However it is intriguing to read through not only the drink recipes, but the formulae for fruit wines, cordials, liqueurs, and bitters that were documented during this early stage in American cocktail making.—Anistatia Miller

Haney’s Steward & Bartender’s Manual was one of many titles Jesse Haney & Co., Publishers produced for the trade. The reason this sample 82-page volume is of interest is because cocktail book collectors such as Mauro Majoub and drinks historians Jared Brown, Anistatia Miller, and Dave Wondrich believe this work may be the book that Harry “The Dean” Johnson referred to as his very first and earliest work. No one will ever know for certain. However it is intriguing to read through not only the drink recipes, but the formulae for fruit wines, cordials, liqueurs, and bitters that were documented during this early stage in American cocktail making.—Anistatia Miller

Drinking Cups & Their Custom

Londoners Henry Porter and George Roberts were not fans of the new American bars nor of cocktails that were displacing traditional British compounds such as punches and cups. By 1860s, the colonial intrusion into British drinking habits insinuated by Reform Club chef Alexis Benoit Soyer, Leo Engels at the Criterion, the Bowling Alley Bar at the Cremorne Pleasure Gardens led these to authors to comment:

Londoners Henry Porter and George Roberts were not fans of the new American bars nor of cocktails that were displacing traditional British compounds such as punches and cups. By 1860s, the colonial intrusion into British drinking habits insinuated by Reform Club chef Alexis Benoit Soyer, Leo Engels at the Criterion, the Bowling Alley Bar at the Cremorne Pleasure Gardens led these to authors to comment:

For the ‘sensation-drinks’ which have lately travelled across the Atlantic we have no friendly feeling . . .we will pass the American bar . . .and express our gratification at the slight success which “Pick-me-up,” “Corpse-reviver,” “Chain-lightning,” and the like, have had in this country.

Generally, British tastes were not attuned to the sweet offerings of the American cocktail menu nor the tooth-numbing coldness at which they were served. Thus, Cups and Their Custom (aka: Drinking Cups and Their Custom) offers a view into a world of lower alcohol strength drinks that rely more on spice and complexity than on heavy citrus and heavier spirit ratios.

Besides wine-based cups and a variety of punches a few other classic British compounds are presented: wassail, lamb’s wool, metheglin, dating back to medieval and Elizabethan times. Ales and beers play a primary role in a few of these concoctions. There are even a handful of essential liqueur recipes as well as a formula for a blood-warming Hunting Flask.

This is the second edition which was published in 1869, the first edition appeared in 1863.

As the bar world looks for inspiration in creating lower-alcohol drinks as well as beer-based offerings, this book becomes a tempting inspiration for drinks development.—Anistatia Miller

1871

Oxford Night Caps

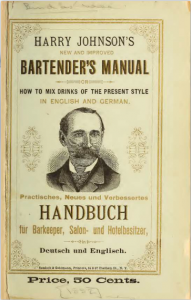

1882

Harry Johnson’s New and Improved Bartender’s Manual

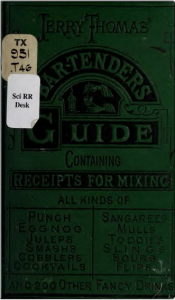

1887

Jerry Thomas’s Bartenders Guide

1888

Harry Johnson’s New and Improved Bartender’s Manual

1892

The Flowing Bowl

New York bartender William Schmidt, nicknamed “The Only William”, commented in his 1892 book The Flowing Bowl that:

New York bartender William Schmidt, nicknamed “The Only William”, commented in his 1892 book The Flowing Bowl that:

“Mixed drinks might be compared to music: an orchestra will produce good music, provided all players are artists; but have only one or two inferior musicians in your band and you may be convinced they will spoil the entire harmony.”

The Only William receives much less attention from historians today than Jerry Thomas and Harry Johnson, yet it could be argued that he was far more famous in his lifetime than either of them.

Born in Hamburg, Germany, William gained fame there as a bartender, and would later state that it was not entirely true that the best bartenders are Americans, or that the best fancy drinks are of American origin. He was quick to point out that he mastered his craft in Hamburg. He also noted that “The finest mixed drinks and their ingredients are of foreign origin. Are not all of the superior cordials of foreign make?”

William, with his small face and giant moustache, arrived, in 1869, in Chicago. By 1873, he took charge of opening the Tivoli Garden with 16 bartenders under him. He was renowned for his acrobatic bartending feats: throwing flaming and non-flaming drinks in graceful arcs. He was even better known for his ability to create drinks that would even convert people who swore they liked nothing stronger than lemonade.

He moved to New York in 1884, where he tended bar at the Bridge Saloon. This may have been its name or simply a geographic monicker, as it was at the Manhattan end of the Brooklyn Bridge and was pulled down a few years later to make way for bridge approaches.

After 20 years behind bars in the US, Schmidt took his first holiday and returned to Hamburg, in 1889, to visit his elderly parents (who were aged 90 and 92 at the time; they passed away the following year). Upon his return to New York, he took on a business partner and opened a place on Broadway near Park Row. When his partner died shortly after, the bar was sold. He stayed on as bartender, through several years and different owners. Eventually the bar was moved to 58 Dey Street, one door west of Greenwich Street, a site that is precisely at the heart of Ground Zero today, as the buildings on that part of Dey Street were torn down to make way for the World Trade Centre.

William was renowned for creating new drinks. And at one point he was estimated to have invented a new one daily. He even created a “$5 cocktail” at a time when drink prices hovered around 15 cents. Sadly, that recipe is lost. He was credited with an encyclopedic knowledge of the classics, but he preferred talking with his customers, then inventing new drinks on the spot to suit their tastes and moods.

He authored two books: Fancy Drinks and Popular Beverages published by Dick & Fitzgerald (who also published Jerry Thomas’ book), in 1891, and a much larger volume, The Flowing Bowl, published by Charles L Webster & Company the following year. Two books from different publishers in such a short time? Not exactly. Fancy Drinks and Popular Beverages simply contains the mixed drink chapters from The Flowing Bowl, which is a much larger book, containing Schmidt’s version of the history of various beverages, descriptions of historic Greco-Roman banquets, samples menus with beverage pairings, plus a lively selection of poetry readings whose focus is on drink.

Despite packing hundreds and hundreds of recipes into his book(s), many of his drinks never made it in. These were often created when a journalist writing about drinks asked him for a classic and, without telling the writer, he created them on the spot. Drinks like the Svengali Cocktail and The Angelus made only into newsprint.—excerpted from Spirituous Journey: A History of Drink, Book Two by Jared Brown & Anistatia Miller (2010)

1893

Fancy Drinks and Popular Beverages

(See description under 1892: The Flowing Bowl.)

1896

Bariana

Bariana

Originally published in 1896, Bariana: Recueil de toutes boissons americains et anglaises, is regarded as one of the earliest-known French cocktail books. It was written by Louis Fouquet, head barman at The Criterion in Paris and later owner of the café that still bears his name. Although the title implies there are many American and British mixed drinks in this volume, there are also creations and variations that are truly unique to France within these pages. The barware that was also illustrated in this volume demonstrates the level of sophistication that Parisien bartenders were able to achieve in the thirty years after mixed drinks made their appearance in French drinking culture around 1862, when the wine industry was stuck a near-fatal blow with the introduction of phylloxera. This French classic was also reprinted in 1902.—Anistatia Miller

1900

Harry Johnson’s Bartenders’ Manual

Harry Johnson’s Bartenders’ Manual

The first book to comprehensively document the proper steps to opening, stocking, and operating a bar, Harry Johnson’s Bartenders’ Manual is a mandatory volume for novices and professionals in the bartending profession. Originally published in 1882, Prussian-born Johnson revised and expanded this book three times (1888, 1900, and posthumously in 1934) as his own knowledge of the business increased.

Containing the first published Martini recipe and the ancestor of the Dry Martini, the Marguerite, Johnson’s recipe collection is a timeline of the American Golden Age of Cocktails. You’ll find the Morning Glory Fizz as well as dozens of early vermouth family cocktails.—Anistatia Miller

1906

Louis’ Mixed Drinks

Louis’ Mixed Drinks

Where do Dry Martinis come from? They were certainly around for a long time before Jacques Louis Muckensturm wrote his 1906 book Louis’ Mixed Drinks. However, Mr Muckensturm will always be remembered as the first person in the English language to call the combination of gin and dry vermouth a Dry Martini. (Frank P Newman echoed the term earlier in French in his 1904 book American-Bar: Boissons Anglaises et Américaine.) Filled with excellent recipes, his book also contains excellent descriptions of the style of wines from different regions, general guidelines that are as accurate and invaluable today as they were a century ago.

Louis’ cocktail recipes exhibit a European influence on his American drinks. His dashes of bitters, maraschino liqueur, curaçao, crème de cassis and many other modifiers reveal a master’s hand and palate.

His chapter on bottled cocktails is fascinating, as this forgotten art is fast emerging as a new trend once again. Other chapters include Fizzes, Highballs, Punches, Cups, layered drinks including a 12-layer Pousse Café, and other surprises such as a recipe for Forbidden Fruit liqueur made from scratch.

Author of Louis’ Mixed Drinks, Louis’ Every Woman’s Cookbook, Louis’ Salads and Chafing Dishes, Muckensturm rose up to become one of America’s top restaurateurs in the early twentieth century. Part of that success might lie in the fact that his restaurant Louis’ Café at 15 Fayette Street in Boston was a family business. His brother Paul was the chef and other family members and even in-laws were employed there. With over 500 seats in the main and private dining rooms, Louis’ played host to countless Boston banquets and fundraisers.

The restaurant was billed as French, though the Muckensturms were a family of hotelkeepers from Alsace, and Alsace was German at that time. During the course of 133 years, the region changed hands between Germany and France five times. Despite these shifts in government, Alsatians tended to keep their own cultural identities. Louis’ family spoke French.

They sailed together aboard the passenger ship La Bourgogne from the Normady port of Havre, arriving in Boston on an unseasonably cool 11 July 1891.

He began as a waiter, until his family pooled enough funds to bankroll his restaurant. As those were the days when a restaurant had to include hotel rooms to be considered respectable, Louis’ Café was in a hotel presumably of the same name, and he stated his profession as hotel proprietor when he registered for the draft during the First World War.

It is not known whether he served in the armed forces. But it is not likely. He passed away, aged 42, from “the grippe”, and was buried in Holyhood Cemetery, resting place Joseph Kennedy and Rose Kennedy, parents of John F. and Robert Kennedy. Louis was survived by his mother, wife, and three brothers.

The bleak realities of Prohibition began to weigh upon the business. In 1921, the bar area was converted to a dance hall, but this could not compensate for liquor revenues. In 1923, his widow Helen spoke publicly about defying the law and continuing to sell alcohol in order to remain in business “because all of their competitors in that neighborhood sell liquor”. Of course, this resulted in a court filing against the restaurant, only the third filed in the state, setting the tone for speakeasies that it was easier to defy the laws quietly than to attempt to challenge them.

What became of Louis’ Café is unknown, but his work lives on around the world in the hands of a new generation of great mixologists.—excerpted from Spirituous Journey: A History of Drink, Book Two by Jared Brown & Anistatia Miller (2010)

1912

Hoffman House Bartender’s Guide

Written by Charles S Mahoney, head bartender of New York’s landmark Hoffman House, The Hoffman House bartender’s Guide gives you a more than ample taste of the cocktail’s golden age in the US during the turn of the century.

Written by Charles S Mahoney, head bartender of New York’s landmark Hoffman House, The Hoffman House bartender’s Guide gives you a more than ample taste of the cocktail’s golden age in the US during the turn of the century.

The Hoffman House was the training ground for such luminaries as Harry Craddock.

Photographs of the Police Gazette‘s annual bartending competition and of some of American’s most famous watering holes makes this volume an inspirational journey back through time.

What did bars operated in New York by Jerry Thomas and Harry Johnson look like on the inside? They were true spectacles: shrines to drink and art. To attract customers, the better places lined their walls with art that now hangs in some of the world’s top museums. Bouguereau’s Nymphs and Satyrs once hung among many other paintings in the Hoffman House. Its proprietor Edward Stokes paid $10,010 USD for it at the time, or roughly $250,000 USD in today’s currency: a fraction of the painting’s current value. Both Thomas’s and Johnson’s personal art collections were reputed to be massive. But we digress.

Hoffman House was equal to Delmonico’s in stature back in the day. An 1893 race between the waiters from the Delmonico’s and Hoffman House restaurants, and those from Cafe Savarin took place in 1893, with each waiter carrying a Manhattan cocktail on a silver tray. Though only the winner got a prize, all competitors got to enjoy their cocktails after the race. But the cocktail was moving a lot faster than a sprinting waiter. By 1895, Manhattans were being served in Japan, Korea, and the Straits of Magellan.

According to Savoy legend Peter Dorelli’s findings in the UKBG newsletters from the 1930s, the young Harry Craddock worked his way from the Hollenden Hotel in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1892, to the Palmer House in Chicago the following year, before taking his post at Manhattan cocktailian hang-out, Hoffman House Hotel: all before joining the esteemed staff at the Knickerbocker Hotel near Times Square at the turn of the century.

The movements of another New York bartender, James B Regan, are also of interest. Who? Haven’t heard of him? Well, he didn’t write a cocktail book, which is what gave virtually every bartender remembered today his fame. But Mr Regan should not be forgotten. As a shoeless boy on the oyster banks of New Jersey, he stood with his father gazing at Manhattan. His father said to him, “I give you all of that—to make good in.”

He found a bar boy job in the old Earle’s Hotel on Canal Street, squeezing lemons. He became a bartender at the Hoffman House Hotel. He became part-owner of the Pabst rathskeller, which stood on 42nd Street between Broadway and Seventh Avenue (the spot where the ball drops every New Year’s Eve). He made the acquaintance of so many wealthy businessmen that when he decided to open his own bar, he simply turned to his best customers to find investors. After a few successful years as proprietor of the Woodmansten Inn in the Bronx, he received an invitation to return to Manhattan. One of his customers, John Jacob Astor was opening a new hotel and proposed that he manage it. On his way to becoming a multi-millionaire himself, Regan went a step further, taking on the Knickerbocker’s lease. And he brought old colleagues like Craddock to work there.

In other words, Hoffman House stood for many years at the fulcrum of many famed bartenders’ careers. It’s worth a read of what they learnt to make before they went onto to fame.—Anistatia Miller

1914

Drinks

Drinks

First published in 1914 and again after Jacqyes Straub’s death in 1920, the slender volume Drinks contains over 700 recipes, including a surprising number of drinks that were thought to have been invented later.

Straub had worked at the Pendennis Club in Louisville, Kentucky, prior to moving to Chicago where he became wine steward for the famous Blackstone Restaurant. Jacques Straub gathered these recipes from both his work and his travels, showing a remarkable palate for the current and future classics of his time.—Anistatia Miller

1918

Distillateur Liquoriste

Distillateur Liquoriste

France is the cradle of European distillation, dating back to the 1200s. By 1918, the artistry and technical expertise of the distiller’s art became the focus of a series of eight books created by the leading publisher of technical and scientific knowledge in France: Encyclopédie-Roret.

Distillateur Liquoriste discloses the formulae and production methods for ingredients that many of today’s craft bartenders are exploring. Dozens of recipes are found in here for: syrups; tinctures; botanical oils; non-alcoholic distilled waters; liqueurs and crèmes in the French, Dutch, German, Italian, British, and American styles; liqueurs hygiénique including Raspail and Arqubeuse recipes; ratafias; vermouths; hypocrisy; and punches.

An untapped wealth of inspiration can be found for making proprietary house ingredients.—Anistatia Miller

1924

Manual del Cantinero

On 9 May 1924, bartenders met in the billiard room at Hotel Ambos Mundo to draft a series of regulations written by Manuel Blanco Cuétara and drafted by attorney Manuel Zavala. After a couple of interim meetings, the final draft of the organisation’s charter was approved by the government on 27 June 1924, registering El Club de Cantineros de la Republica de Cuba in the Special Register of Associations with Ambos Mundo’s José Cuervo Fernandez as president and Cristóbal Blanco Alvarez as secretary-general. Within its first six months, the Club sported 121 members.

On 9 May 1924, bartenders met in the billiard room at Hotel Ambos Mundo to draft a series of regulations written by Manuel Blanco Cuétara and drafted by attorney Manuel Zavala. After a couple of interim meetings, the final draft of the organisation’s charter was approved by the government on 27 June 1924, registering El Club de Cantineros de la Republica de Cuba in the Special Register of Associations with Ambos Mundo’s José Cuervo Fernandez as president and Cristóbal Blanco Alvarez as secretary-general. Within its first six months, the Club sported 121 members.

Nine years before the United Kingdom Bartenders Guild—frequently cited as the world’s first bartender’s association—was established by a group of London bartenders, the Club set about to train a new generation of Cuban-born professions to live up to journalist Hector Zumbado’s eloquent description:

“They have the elegance of a symphony conductor, the precision and calm of a surgeon ready to operate. They are the chemists of today, the botanists of the eighteenth century, the alchemists of the Middle Ages, capable of willing the creation of cool, shining gold. They are experts in the topics of sport and international politics, but they never give in to passionate discourse. …They need the memory of elephants for they must remember how to make, without looking them up, between 100 and 200 cocktails.”

Bartender-teachers Don Jose Maria Vazquez Prieto, Manuel Taboada and auxiliary Fabio Delgado were not the only instructors who drilled new students on the proper making of cocktails. Humberto Martin, Artemio Prieto , José Perales and the co-author of the official Manual del Cantinero León Pujol also contributed their knowledge and expertise.

Subsequent cantinero manuals grew in size and depth of knowledge, published in the 1930 Club de Cantinero de la Republica de Cuba: Manual Oficial and 1948 El Arte del Cantinero. The recipes in this first manual are simple and to the point, making them easy to memorise, which each certified cantinero did.—Anistatia Miller

1926

The Cocktail Book: A Side Board for Gentlemen

The Cocktail Book: A Side Board for Gentlemen

Published during the cocktail’s heyday in Great Britain, this small volume—The Cocktail Book: A Sideboard for Gentlemen—demonstrates what every good private valet to any of London’s Bright Young People needed to know how to mix, shake, or stir between the two Great Wars.

Cocktails, smashes, cobblers, punches, cups, and the entire mixed drink repertoire including wine selection for dinner are to be found in this priceless volume.—Anistatia Miller

1927

El Arte de Hacer un Cocktail y Algo Mas

El Arte de Hacer un Cocktail y Algo Mas

The American invasion of Havana during the 1920s was not limited to thirsty citizens quenching their desire for cocktails on this Caribbean island. Breweries such as Cervecera International were established by partnerships formed with former American beer companies. Published by this large brewing house in 1927, El Arte de Hacer un Cocktail y Algo Mas displays what sort of mixed drinks both Cuban and transplanted American bartenders were offering customers in bars across Cuba.—Anistatia Miller

1928

When It’s Cocktail Time in Cuba

When It’s Cocktail Time in Cuba

Privately published in 1928 by Horace Liveright, British playwright and journalist Basil Woon captured the energy the take hold of Havana, as Americans flocked by the thousands to drink, gamble and party amid the tropical beauty that is Cuba.

Of special interest to bartenders is Chapter 2, in which he describes in detail the daily gathering at the rooftop bar in the Sevilla-Biltmore Hotel. There, Eddie Woelhke and Fred Kaufman presided over the mixing not only of classic Cuban cocktails, but some of their own creation.—Anistatia Miller

193o

Club de Cantinero de la Republica de Cuba: Manual Oficial

Six years after El Club de Cantineros de la Republica de Cuba was registered with the Cuban government as a legitimate professional association and issued its first Manual del Cantinero, a more in-depth volume. Club de Cantinero de la Republica de Cuba: Manual Oficial by Gerardo Corrales provides reference material on the origins of various wines, food service pairings, and types of service glassware were included in the text along with hundreds more recipes for cocktails and mixed drinks. It took another eighteen years for the accumulated knowledge of bartending, wines, spirits and mixed drinks in Cuba culminated in the gigantic bible El Arte del Cantinero—Anistatia Miller

Six years after El Club de Cantineros de la Republica de Cuba was registered with the Cuban government as a legitimate professional association and issued its first Manual del Cantinero, a more in-depth volume. Club de Cantinero de la Republica de Cuba: Manual Oficial by Gerardo Corrales provides reference material on the origins of various wines, food service pairings, and types of service glassware were included in the text along with hundreds more recipes for cocktails and mixed drinks. It took another eighteen years for the accumulated knowledge of bartending, wines, spirits and mixed drinks in Cuba culminated in the gigantic bible El Arte del Cantinero—Anistatia Miller

1931

Cuban Cookery

Yes. This is a cookbook. It is a Cuban cookbook filled with some great recipes to tantalise your tastebuds for Criollo cuisine. But it is the appendix to Cuban Cookery that most appeals to bartenders. The appendix starts on page 119 and contains not only obvious Cuban classics but some that are rarely seen such as the Grapefruit Blossom, Creole Cocktail, and a rum Cocktail (also called a Cuban Mojo).—Anistatia Miller

Yes. This is a cookbook. It is a Cuban cookbook filled with some great recipes to tantalise your tastebuds for Criollo cuisine. But it is the appendix to Cuban Cookery that most appeals to bartenders. The appendix starts on page 119 and contains not only obvious Cuban classics but some that are rarely seen such as the Grapefruit Blossom, Creole Cocktail, and a rum Cocktail (also called a Cuban Mojo).—Anistatia Miller

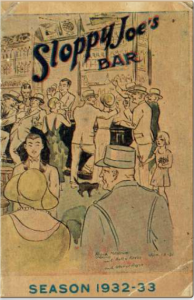

1932

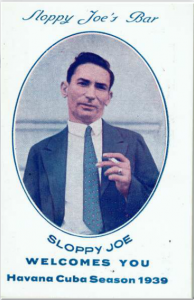

Sloppy Joe’s Bar

No less than 37 stools and all are taken! Such was the impressive spectacle that lay before Sloppy Joe’s two master cantineros. This perennially crowded bar on Animas Street between Prado and Zulueta Streets was a requisite destination from the 1930s to the 1960s for any visitor to Havana.

No less than 37 stools and all are taken! Such was the impressive spectacle that lay before Sloppy Joe’s two master cantineros. This perennially crowded bar on Animas Street between Prado and Zulueta Streets was a requisite destination from the 1930s to the 1960s for any visitor to Havana.

José Abeal y Otero arrived in Havana from Spain in 1904 and took a bartending job at the corner of Galiano and Zanja Streets. After three years, he packed his bags and set sail for New Orleans where he honed his skills behind the bar. Then he stopped in Miami where he continued to practice his craft.

As the legend was told in the 1936 edition of Sloppy Joe’s Bar:

” In the year 1918, he returned to Havana and got a job as a bartender at a café named ‘Greasy Spoon’ and six months after, he decided to go into business for himself and bought what was then an insignificant bodega [grocery store] at the same corner now occupied by Sloppy Joe’s.

“While operating this small grocery store, he was visited by several of his old friends from the States. It so happened that while some of them were visiting him and seeing the poor appearance and filthy looking condition of the place one of them said: “Why Joe, this place is certainly sloppy. Look at the filthy water running from under the counter.”

Nestled between the fashionable Plaza and Sevilla hotels, José and his partner Valentin Garcia initially sold liquor and sundry groceries. Business developed rapidly and in a very short time, they opened the elongated bar. Sloppy Joe’s had a reputation. One day, an American journalist who lost a wad of money during one drinking session was quite moved and grateful to find his wallet and its entire contents at the bar the next day.

Thanks to this news item, American servicemen based in San Antonio de los Banos made Sloppy Joe’s one of their regular hangouts. As soon as they arrived in the trusted establishment, the GIs put their money on the bar and start drinking. As drinks were served, the cantineros drew payment from the stack until the funds ran out or the drinkers staggered out.

There are some interesting surprises to be found in these small souvenir booklets. Recipes for both a Daiquiri and a Santiago (it’s close cousin) can be found back to back. Two Presidente variations, both gin and rum versions of a Mojito, and 14 “Special Cocktails” including the signature Sloppy Joe’s Cocktail are worth a perusal.—Anistatia Miller

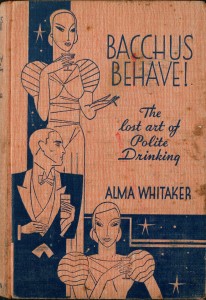

1933

Bacchus Behave!: The Lost Art of Polite Drinking

Bacchus Behave!: The Lost Art of Polite Drinking

Los Angeles Times’ gossip columnist Alma Whitaker wrote the lovely, witty tome on post-Prohibition drink and drinking—Bacchus Behave! The Lost Art of Polite Drinking—adding with more than a few blurbs from film director Rupert Hughes, actors Clark Gable, Charles Chaplin, Marie Dressler, Tom Mix, and blockbuster producer Cecil B. De Mille.

As you can gather from this list of contents, Whitaker has a few veteran words to less-wise new American drinkers:

—In Which We Discuss Nectar

—Nectar & Manners

—Simple Rules For Righteous Behaviour

—Cocktails

—Whiskey

—Gin

—Brandy

—Liqueurs

—Wines

—Rum

—Champagne

—Beer

—Hints To Hostesses

—On Being A Good Guest

—Customs To Frown Upon

—Strange Nectars

—Canapés & Hors-D’oeuvres

—The Buffet Supper

—Punches & Cups

—notes by Anistatia Miller

1934

Jayne’s Bartender’s Guide

Jayne’s Bartender’s Guide

With an anonymous author and published by Dr D Jayne and Son in Philadelphia circa 1934, Jayne’s Bartender’s Guide was one of many books published right after the repeal of Prohibition in the USA that hoped to revive the recipes and the culture of cocktail drinking after a nearly 15-year hiatus. In addition to recipes for cocktails and mixed drinks, there are also formulae for making some long-lost ingredients such as Stoughton’s Bitter, Angostura Bitters, Orange Bitters, Usquebaugh Cordial, and loads of other curiosities.—Anistatia Miller

Cocktails: Bar La Florida

Sloppy Joe’s Bar

1935

Cocktails: Bar La Florida

1936

The Artistry of Mixing Drinks

The Artistry of Mixing Drinks

One thousand copies of Frank Meier’s The Artistry of Mixing Drinks were published in 1936. As a bartender in one of the world’s most exclusive venues of the time, the Paris Ritz, where he worked from 1921 to 1947, Meier had amassed an impressive, loyal following of celebrities and other notables as well as the businessmen and boldface names of Parisian society.

The release of his book mirrored the layers of social strata among his customers: 26 copies lettered A to Z were specially printed along with an additional 300 numbered copies on handmade paper. An additional 700 copies were printed on cream vellum paper—still made with care, but not precious enough for the cream of his crop.

Meier’s The Artistry of Mixing Drinks contains nearly 500 drink recipes, including over 40 marked as his own personal creations. He included advice on wine regions and vintages, three-dozen sandwich recipes, bartending tips and tricks.

But Meier had a restless mind. And this was his book. There is a primer on horse racing, antidotes for poisons, a world time zones chart, nautical mile conversions, the circumference of the earth in feet and miles plus the planet’s surface area, the deepest point in the ocean and the height of Everest.

Need to calculate the carat weight of a diamond or a pearl? Work out the measure of a bolt of silk in yards or nails? Wondering what the lbs per square foot pressure is from a brisk gale? Need to remove stains from an oil painting? Meier even included instructions on how to aid a drowning victim, someone struck by lighting or bitten by a snake.

The Artistry of Mixing Drinks is so much more than a cocktail book, and it is our great honor to bring it back into print for the first time since those 1000 copies passed through Meier’s hands and into bartending history.—Anistatia Miller

Sloppy Joe’s Bar

1000 Misture

The cocktail was something really new in Italy during the 1920s and 1930s. After 2000 years of ippocratic wines , bitters and finally Vermouth served in a super classic way (the old style with just a lemon zest or a splash of soda), Italian barmen began to really to understand and incorporate cocktail culture imported from the rest of the world into their drink menus.

The cocktail was something really new in Italy during the 1920s and 1930s. After 2000 years of ippocratic wines , bitters and finally Vermouth served in a super classic way (the old style with just a lemon zest or a splash of soda), Italian barmen began to really to understand and incorporate cocktail culture imported from the rest of the world into their drink menus.

Elvezio Grassi, a real globetrotting bartender, compiled an incredible collection of recipes captured in his experiences from his travels and the books he collected from all around the world mixed with his own amazing Italian style.

Mille Misture will open your mind about how incredible and various Italian bartending culture has been for years. You will find the amazing Americano family before the classic moderno standard was established and a lot of interesting and some times bizarre mixtures to try.—Leonardo Leuci, 2014

1937

Café Royal Cocktail Book

Originally published in 1937 by the United Kingdom Bartenders Guild, Café Royal Cocktail Book compiled by William J Tarling offers a rare glimpse into the wide array of drinks offered in London bars between the two world wars. Tarling, head bartender at the Café Royal during had two goals. He wanted to extend this resource to consumers. Serving as Guild president after Harry Craddock, he also wanted to raise funds for the United Kingdom Bartenders Guild Sickness Fund and the Café Royal Sports Club Fund.

Originally published in 1937 by the United Kingdom Bartenders Guild, Café Royal Cocktail Book compiled by William J Tarling offers a rare glimpse into the wide array of drinks offered in London bars between the two world wars. Tarling, head bartender at the Café Royal during had two goals. He wanted to extend this resource to consumers. Serving as Guild president after Harry Craddock, he also wanted to raise funds for the United Kingdom Bartenders Guild Sickness Fund and the Café Royal Sports Club Fund.

Thus, Tarling drew from the recipes previously compiled for Approved Cocktails, and added more—hundreds more—collected from his contemporaries, competitions, and his own personal file box. The result was an outstanding and timely book.

The Café Royal Cocktail Book did more than gather recipes, it captured a boom time in the history of cocktails, glass by glass. Sadly, there was only one printing and it became an unobtainable rarity, locking away a time capsule of drinks and knowledge.

Within these pages are some of the earliest known recipes for drinks made with tequila and vodka as well as memorable concoctions made with absinthe and other recently revived ingredients-an essential addition to every cocktail book library.—Anistatia Miller

Cocktails: Bar La Florida

1939

Famous Orleans Drinks and How to Mix ‘Em

One of the greatest historical cocktail destinations to be found, New Orleans has been the birthplace of many a classic compound: Sazerac, the Vieux Carré, Ramos Gin Fizz, Grasshopper, the list is endless. Written by journalist and Louisiana historian Stanley Clisby Arthur, Famous New Orleans Drinks and How to Mix ‘Em is a delightful travel guide to not only New Orleans creations and variations, but to some of the exports that arrived from another nearby landmark drink centre: Cuba. This is the third edition of this well-loved tome.

One of the greatest historical cocktail destinations to be found, New Orleans has been the birthplace of many a classic compound: Sazerac, the Vieux Carré, Ramos Gin Fizz, Grasshopper, the list is endless. Written by journalist and Louisiana historian Stanley Clisby Arthur, Famous New Orleans Drinks and How to Mix ‘Em is a delightful travel guide to not only New Orleans creations and variations, but to some of the exports that arrived from another nearby landmark drink centre: Cuba. This is the third edition of this well-loved tome.

Next to the Tchoupitoulas Street Guzzle is the Cuban Rainbow Pousse Café as it was served at Sloppy Joe’s in Havana. We think you’ll find the recipes for the Daiquirí and the Barcardí Cocktails on page 60 eye-opening.

Arthur’s take on the New Orleans birth of the cocktail was the stuff of legend (pages 9-14) until present-day cocktail historians uncovered broader truths. Nevertheless, Arthur brings to life the drinks that made New Orleans famous and provides insights into the city’s history through its drinks.—Anistatia Miller

1939

Cocktails: Bar La Florida

Cocktails: Bar La Florida

El Floridita (an endearing diminutive for the phrase La Florida) is at the top of countless bartenders and cocktailians’ list of watering holes to visit within their lifetimes. And of course, that visit includes sipping a Daiquirí, as Floridita is recognised as the birthplace of a few classic Daiquirí variations.

As a promotion, the bar published a small booklet of its recipes: Cocktails—Bar La Florida. This particular volume is the 1939 edition. (The 1934, 1935, and 1937 can be found above.)

Hemingway drank there so often that a life-size bronze statue of Papa occupies his spot at the end of the bar. The place hasn’t changed much since Constantino Ribalaigua Vert took over ownership in 1918, when owner Don Narcisco Parrera retired.

The bar team’s uniforms are the same. The menu has hardly varied. The décor looks surprisingly like it does in the vintage photos on the walls. This (thanks in no small part to the everlasting US trade embargo with Cuba) has preserved the perfection Constante created. He was also kind enough to write down his recipes and publish them in a souvenir book printed just a few times during the 1930s.

Here are all the Cuban classics, plus some drinks you might never expect to find in Cuba if not for thirsty Americans supplying a Prohibition-era demand for them. Drinks such as the Mary Pickford and El Presidente are all here. It’s cocktail time in Cuba!—Anistatia Miller

Floridita Cocktails

Bar La Florida had gained international status after Constante Ribalaigua Vert inherited the Havana bar-restaurant in 1918 from owner Don Narcisco Sala Parera. Every year, beginning in 1934, La Florida gave away souvenir booklets of the recipes that tempted visitors from around the globe and captured the hearts of celebrities such as Ernest Hemingway.

Bar La Florida had gained international status after Constante Ribalaigua Vert inherited the Havana bar-restaurant in 1918 from owner Don Narcisco Sala Parera. Every year, beginning in 1934, La Florida gave away souvenir booklets of the recipes that tempted visitors from around the globe and captured the hearts of celebrities such as Ernest Hemingway.

The bar earned a new name by the end of the 1930s, El Floridita. And although Constante had already printed the 1939 edition of his Cocktails: Bar La Florida booklet, he published this particular with the venue more familiar name. Floridita Cocktails contains precisely the same history, anecdotes, and recipes found in the previous editions with one exception.

This volume contains nine new drinks: Mauro Special, Ing Armando J Valdes Special, Carmen Morell Special, Pepe Blanco Special, Josefina Prieto Special, Natividad, Ginebra Compuesta, Mr Solar Special, and the soon-to-become classic Jai-Alai.—Anistatia Miller

The Gentleman’s Companion, Volume II: An Exotic Drinking Book

In 1931, American journalist Charles H Baker Jr took an odyssey, searching for the finest food and drink in such obscure corners as Cairo, Mindinao, Calcutta, Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Borneo, Jaipur, and Yokohama. Everywhere he went, everywhere he looked there was a bar, a bartender, and some unique, carefully prepared variation on the words “cocktail” and “mixed drink.” Thus was found the material documented in The Gentleman’s Companion, Volume II: An Exotic Drinking Book

In 1931, American journalist Charles H Baker Jr took an odyssey, searching for the finest food and drink in such obscure corners as Cairo, Mindinao, Calcutta, Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Borneo, Jaipur, and Yokohama. Everywhere he went, everywhere he looked there was a bar, a bartender, and some unique, carefully prepared variation on the words “cocktail” and “mixed drink.” Thus was found the material documented in The Gentleman’s Companion, Volume II: An Exotic Drinking Book

Even in the wilds of Siberia, Baker discovered a vodka concoction whose descendant became a resounding 1970s hit—The Vladivostok Virgin.

While in Buenos Aires, wandering journalist met “two young gentlemen from the Argentine . . .and who own polo ponies, ranches, and things.” He tried the gentlemen’s Mi Amante during a local heat wave “with results entirely at odds with the first reaction to its written formula.”

Baker was told the tale of the Daiquiri from a somewhat different perspective than other journalists and authors relate, adding a few more characters to the plot.

He also explored a different and wholly imaginative recipe for the Singapore Sling and a possible ancestor of the Martini known as the San Martin.

Eight years later, when he published his notes in his 1939 book The Gentlemen’s Companion: Being an Exotic Drinking Book or, Around the World with Jigger, Beaker, and Flask, he documented how deeply the cocktail had become engrained in the world’s minds and hearts. Even cocktails with familiar names had personal twists that made the drink the particular bartender’s own. The global industry had reached a point in which customised classic were the norm, locally-sourced ingredients replaced hard-to-get originals, and proportions were adjusted to suit local tastes. The true creativity of cuisine had reached its zenith, albeit hidden from public scrutiny because celebrity names weren’t attached to their consumption or creation.

The stories alone in this volume are a travelogue for bartenders and sippers to savour page by page, drink by drink. And the surprisingly different versions of some of the world’s favourite concoctions are a study on their own.—Anistatia Miller

Sloppy Joe’s Bar

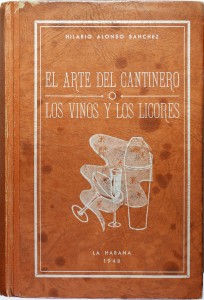

1948

El Arte del Cantinero

Published in 1948, El Arte del Cantinero was compiled and written by cantinero Hilario Alonso Sáchez who had established in 1911 the Employees Union Café and was an active component of the Club del Cantineros of Cuba, teaching, lobbying for the legal rights of bartenders, and serving as the club’s chief chronicler and historian.

This particular edition, unlike its 1924 predecessor—Manual del Cantinero—contains an encyclopaedic knowledge of the history of spirits and wine production; alcohol and alcoholism; histories of glassware, bottles, and ice; a compendium of the many origins of the cocktail that were being bantered around at the time; the histories of some major drink repines as they were told in bars at the time; and in particular the reprint of a very eye-opening letter sent by Federico D Pagliuchi, an engineer and one of the leaders of the liberation army, to the editor of El Pais, correcting the origins of the Daiquirí.

A full discussion of what it means to be a professional cantinero and a Cuban version of how to stock and operate a bar that stands shoulder to shoulder with Harry Johnson’s Bartenders’ Manual as a timeless manual that is still relevant today.

Hundreds of recipes and service tips complete this bible of Cuban bartending, which is a must-read for every person in this industry.—Anistatia Miller

The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks

He may never have worked behind that stick in his entire life, but David A Embury contributed to the bartending profession his passion for cocktails and his obsession in understanding their true nature. In his seminal 1948 work The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks Embury spells out in no uncertain terms the structure of the six basic cocktails: Martini, Manhattan, Old-Fashoined, Daiquiri, Side Car, and Jack Rose along with all of their attendant variations.

He may never have worked behind that stick in his entire life, but David A Embury contributed to the bartending profession his passion for cocktails and his obsession in understanding their true nature. In his seminal 1948 work The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks Embury spells out in no uncertain terms the structure of the six basic cocktails: Martini, Manhattan, Old-Fashoined, Daiquiri, Side Car, and Jack Rose along with all of their attendant variations.

He details to a finite degree the ingredients, liquors, bar equipment and serving vessels that make up the modern bar and how to use them. Where Harry Johnson outlines the operation of the bar and the proper way to provide great service, Embury outlines the mechanics of making classics, introduces modern variations, and offers the best base for creating new recipes built upon a solid understanding of what makes each style of drink unique in the drinks family tree.

This is not a dry text by any means, Embury’s writing style is conversational, humorous, serious, and ultimately engaging. A New York attorney, he openly admitted that his experience with mixed drinks was : “entirely as a consumer and as a shaker-upper of drinks for the delectation of my guests”

Embury achieved such remarkable public popularity for this work, that 21 Club barman Jack Townsend wrote a deliciously curmudgeonly cocktail book in retaliation. You see, Embury was one of his regular customers. When the young attorney announced the publication of his own book, the elder bartender was pea green with envy!—Anistatia Miller

[Please note that the above title is not available for viewing.]

Ron Daiquirí Coctelera Cocktail Book

This slim 32-page volume, Ron Daiquirí Coctelera Cocktail Book, is a real fascination. Ron Daiquirí rums appear more than dozen times in such classic bar books as the 1930 Savoy Cocktail Book. So its popularity made it overseas at the height of the 1920s London cocktail scene. How popular was this rum? The company had an exhibition room at 66 O’Reilly Street in Old Havana where tourists could sample the distillery’s product line and sip a Daiquirí. By the 1940s, this was not a unique way to sell rum. Bacardí and Havana Club had been serving tourists free cocktails and tastings since the 1930s. What was unique was this little souvenir booklet presented five hints for the novice mixer, a suggested list of sideboard ingredients to have on hand for guests, and an illustrated explanation of how Ron Daiquirí Coctelera Rums were produced. —Anistatia Miller

This slim 32-page volume, Ron Daiquirí Coctelera Cocktail Book, is a real fascination. Ron Daiquirí rums appear more than dozen times in such classic bar books as the 1930 Savoy Cocktail Book. So its popularity made it overseas at the height of the 1920s London cocktail scene. How popular was this rum? The company had an exhibition room at 66 O’Reilly Street in Old Havana where tourists could sample the distillery’s product line and sip a Daiquirí. By the 1940s, this was not a unique way to sell rum. Bacardí and Havana Club had been serving tourists free cocktails and tastings since the 1930s. What was unique was this little souvenir booklet presented five hints for the novice mixer, a suggested list of sideboard ingredients to have on hand for guests, and an illustrated explanation of how Ron Daiquirí Coctelera Rums were produced. —Anistatia Miller

1959

Manzarbeitia y Compania Cocktail Book

Cocktails were so popular in Havana by the late 1950s, even distributors such as Manzarbeitia y Compania got on the bandwagon. In 1959, the company published a hardcover cocktail book that featured recipes using its broad portfolio of spirits. The Manzarbeitia y Compania Cocktail Book offers up wines, spirits, liqueurs, beer, cider, aguardiente, amaros, bitters, anise spirits, recipes (including a few wine-based mixed drinks), equipment lists, and tips for professionals and home mixers. But no where in this red velvet covered Cuban cocktail book is there a single rum recipe!—Anistatia Miller

Cocktails were so popular in Havana by the late 1950s, even distributors such as Manzarbeitia y Compania got on the bandwagon. In 1959, the company published a hardcover cocktail book that featured recipes using its broad portfolio of spirits. The Manzarbeitia y Compania Cocktail Book offers up wines, spirits, liqueurs, beer, cider, aguardiente, amaros, bitters, anise spirits, recipes (including a few wine-based mixed drinks), equipment lists, and tips for professionals and home mixers. But no where in this red velvet covered Cuban cocktail book is there a single rum recipe!—Anistatia Miller

(See description under 1862).

(See description under 1862).

(See description under 1932.)

(See description under 1932.)

4 Comments

[…] Dispensatory would possibly seem to be an odd textual content, nonetheless, to incorporate in an online library for bartenders, however it’s completely in line with the spirit of the EUVS Digital Collection, an […]

Endless hours of fabulous stuff!

Thank you massively

[…] A Digital Online Library for Bartenders found via Open Culture. […]

As a bartender, I resonate deeply with the idea that “The art of the cocktail is like the art of storytelling—both require balance, creativity, and a touch of magic.” Your platform beautifully captures this essence, bridging mixology with literature in a way that is both inspiring and educational.