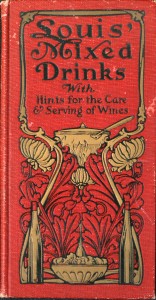

Louis’ Mixed Drinks by Muckensturm (1906)

Where do Dry Martinis come from? They were certainly around for a long time before Jacques Louis Muckensturm wrote his 1906 book Louis’ Mixed Drinks. However, Mr Muckensturm will always be remembered as the first person in the English language to call the combination of gin and dry vermouth a Dry Martini. (Frank P Newman echoed the term earlier in French in his 1904 book American-Bar: Boissons Anglaises et Américaine.) Filled with excellent recipes, his book also contains excellent descriptions of the style of wines from different regions, general guidelines that are as accurate and invaluable today as they were a century ago.

Louis’ cocktail recipes exhibit a European influence on his American drinks. His dashes of bitters, maraschino liqueur, curaçao, crème de cassis and many other modifiers reveal a master’s hand and palate.

His chapter on bottled cocktails is fascinating, as this forgotten art is fast emerging as a new trend once again. Other chapters include Fizzes, Highballs, Punches, Cups, layered drinks including a 12-layer Pousse Café, and other surprises such as a recipe for Forbidden Fruit liqueur made from scratch.

Author of Louis’ Mixed Drinks, Louis’ Every Woman’s Cookbook, Louis’ Salads and Chafing Dishes, Muckensturm rose up to become one of America’s top restaurateurs in the early twentieth century. Part of that success might lie in the fact that his restaurant Louis’ Café at 15 Fayette Street in Boston was a family business. His brother Paul was the chef and other family members and even in-laws were employed there. With over 500 seats in the main and private dining rooms, Louis’ played host to countless Boston banquets and fundraisers.

The restaurant was billed as French, though the Muckensturms were a family of hotelkeepers from Alsace, and Alsace was German at that time. During the course of 133 years, the region changed hands between Germany and France five times. Despite these shifts in government, Alsatians tended to keep their own cultural identities. Louis’ family spoke French.

They sailed together aboard the passenger ship La Bourgogne from the Normady port of Havre, arriving in Boston on an unseasonably cool 11 July 1891.

He began as a waiter, until his family pooled enough funds to bankroll his restaurant. As those were the days when a restaurant had to include hotel rooms to be considered respectable, Louis’ Café was in a hotel presumably of the same name, and he stated his profession as hotel proprietor when he registered for the draft during the First World War.

It is not known whether he served in the armed forces. But it is not likely. He passed away, aged 42, from “the grippe”, and was buried in Holyhood Cemetery, resting place Joseph Kennedy and Rose Kennedy, parents of John F. and Robert Kennedy. Louis was survived by his mother, wife, and three brothers.

The bleak realities of Prohibition began to weigh upon the business. In 1921, the bar area was converted to a dance hall, but this could not compensate for liquor revenues. In 1923, his widow Helen spoke publicly about defying the law and continuing to sell alcohol in order to remain in business “because all of their competitors in that neighborhood sell liquor”. Of course, this resulted in a court filing against the restaurant, only the third filed in the state, setting the tone for speakeasies that it was easier to defy the laws quietly than to attempt to challenge them.

What became of Louis’ Café is unknown, but his work lives on around the world in the hands of a new generation of great mixologists.—excerpted from Spirituous Journey: A History of Drink, Book Two by Jared Brown & Anistatia Miller (2010)